Let's start with number 10.

10. Risk

|

"The game of world conquest" dates from 1957 and the Cold War atmosphere

shows. An important precept has developed since those days: Everybody

Plays, and has a chance to win, right until the end. But not in

Risk, where players can be eliminated hours before it's over.

Then too, it features a cards collecting

mechanism designed to help out those with smaller board holdings, but

whoever is luckiest at collecting cards receives the most reinforcements and tends to do the best.

Much of the strategy is in deciding when the odds favor taking a

particular player out of the game and thus receiving more cards to

cash in for extra armies. While there is plenty of excitement, there

is little profit in long-term planning and the best strategy often

does not correspond with victory.

It's high time to put this warhorse out to pasture.

|

9. Pictionary

|

This curious list takes us from one extreme, the war game, all the way

to the other, a party game, in this

case dating back to 1985. As you probably know, it's all about

drawing a picture of a random word while others guess it in a

limited timespan. Drawing skill is rewarded as is players

knowing one another well. Objects are easy, but some words, e.g.

"wide", can prove quite challenging and stimulating to creativity.

It's not entirely without problems. When two or more groups are

playing at the same time it can be difficult to tell who finished first,

not to mention the possibility of unscrupulous players who train their

eyes on their artist's picture, but their ears on the guesses of other

teams. This is a communication game and humans are so creative in

communication that facial and hand gestures can sneak in,

definitely against the rules, but difficult to entirely rule out.

At times it can drag on too long as well. But the main goal of the

party game: getting people to relax, reveal a bit of themselves and

have some great laughs is almost always achieved.

|

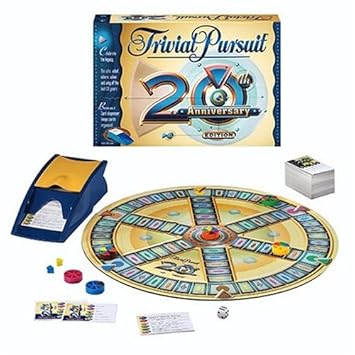

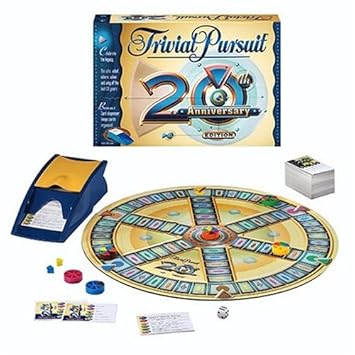

8. Trivial Pursuit

|

Continuing with another 80s party game (1981), we come to a game of

knowledge and pop culture. Although generally a bit more tame than

Pictionary, it has the same power to bring out many of the same

outbursts and emotions. Presenting a very clear picture of each

player's progress (using innovative playing pieces that build over

time), finding the sweet spot of easy and not-so-easy questions and

not lasting past the point of player patience are a few of the things

that this does so well.

|

7. Othello

|

With Othello we go back to the 80s, 1880, that is.

Originally called Annexation or Annex this two-player abstract

flickered out, only to return to popularity and gain its semi-classic

status in the 1950s.

A likely descendant of

Go

it differs in that there is a white side and a black side to each

token, the object being to outflank the opponent by getting own disks

on both ends of a line. This flips the opponent's disks to the acting

player's color. Although flavorless and lacking in variety, there is

certainly strategy and plenty for the mind to chew on. Simple rules

and setup certainly contribute a lot to its accessibility; anyone can

sit down and without much explanation, just start playing.

|

6. Cluedo/Clue

|

Dating to 1949, Clue probably owes a lot to Agatha Christie,

A. Conan Doyle and also World War II. A topic as outré as murder had been

rare in board games, but the worst war the world had ever seen

desensitized the audience in such matters. (You can see similar trends

in the movies of the period.) Although

subsequent games have taken its focus on logical deduction further, it

can still often mostly work. Probably there are not enough die rolls

in the game for probabilities to work out fairly and a player who rolls

consistently badly can be a disadvantage. In addition players probably

have too much control over others, being able to pick up their pieces

and move them to wherever they are on the board. If the table

considers a particular player the most likely suspect, even if wrongly so,

they tend to lose control of their fate. Still, the character

personalities and the English mansion setting have become iconic and

delicious. It plays much better when players also note

the results of card reveals in which they are not involved.

|

5. Monopoly

|

The original version dates from 1904, among gamers this is probably the most

controversial game in this list. Some continue to love it while the rest

have left it far behind. Its supporters like to point out that few

play it as intended – so many use

variants

such as placing tax

payments to be claimed on Free Parking and the omission of the auction

rules for unpurchased properties. These lengthen play time quite a bit

and contribute not a little to the general dislike, which tends to

make the game's fans even more adamant. But they have to admit there

are other serious problems. Players are eliminated. The first player

has an unfair advantage because the earlier you roll the better property

purchasing opportunities you have. The two card decks are rather

unbalanced. This game can be so frustrating that it is probably the

game second most responsible for flipped boards in history.

Those who cherish it probably do so more because it is

the first such money and strategy game they ever played than for

rational reasons. But they are in the minority. With the rest this one has

generated hatred, not just for it, but by association for all strategy

games, the best reason of all to just let it go.

|

4. Scrabble

|

The classic word game from 1931 is not only about vocabulary,

but also strategy since the board has a definite geography in terms of

double and triple letter and word spaces. It would be great if it

were about knowing lots of different words and being good at

figuring out what you can make with your letters, but developing

proficiency in this one goes in the wrong direction. Most experts

tend to form very short words to limit severely the choices of

opponents. Fanatics memorize every obscure two- and

three-letter word in the official dictionary (words never used in real

life), an artifact of play which tends to be a polarizing factor in its

popularity. Finally, because of deficiencies in the challenge system,

strictly speaking this only works in the two-player situation.

|

3. Backgammon

|

This abstract is a true

classic, apparently dating back five thousand years to

Mesopotamia. It may share a common ancestor with Pachisi,

was probably related to the Egyptian game Senet and spread

everywhere by Roman legions. Popularity surged in the United

States during the 1970s and continues today, probably for the

gambling element. Like Othello it is also quite easy to learn.

The gambling aspect saves the game's main problem, its extreme

vagaries of luck. The only way to really play it is to make an entire

evening of a series of games, gambling on the outcome of each match,

the smart player will then usually do better because he can tell when

to raise the stakes and when to refrain.

But a single playing or two, the only possible circumstances for most,

is bound to be just a disappointing exercise in dice luck.

|

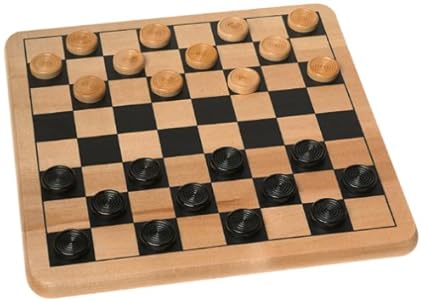

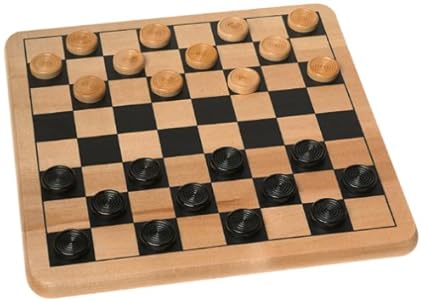

2. Checkers

|

Here is another true oldie, an

abstract whose roots stretch all the way back to ancient Egypt, when

possibly it was not quite so abstract. Today, versions vary and the UK

and USA seem content to play on a 8x8 board while continental Europe

prefers a 10x10 board. Other parts of the world, such as

southeast Asia, even use 12x12. Generally quite popular,

although somehow lacking the exalted reputation of Chess, to which it

is often compared, probably on the basis of the similar board even

though this is not really appropriate as the two are quite different.

Admittedly quite accessible,

this game has been "solved", in the sense that computer analysis has

determined everything that can be known about it, even determining

that the first player has a slight advantage. If that doesn't

discourage, when it comes to both flavor and variety, it's rather

lacking.

|

1. Chess

|

The last of the true oldies has

obviously experienced a large number of

rules changes over time. Allowing pawns to optionally move

forward two spaces is a fix to speed things up while the en passant

rule is a fix to this fix. Strategy is very deep, but computers

are beating even the very best players these days.

Unlike many of the games above, there is no luck apart from who

starts. Despite its former reputation as a quaint, sissy pursuit, it

is increasingly becoming recognized, for example as in The Joy Luck

Club, that good play is mostly about aggression. As with the similarly

popular Bridge, the very extensive amount of literature about the game

prove to be its downfall. In the words of Baldassare Castiglione who

wrote his Etiquette for Renaissance Gentlemen in 1528: "That is

certainly a refined and ingenious recreation," said Federico, "but it

seems to me to possess one defect; namely, that it is possible for it

to demand too much knowledge, so that anyone who wishes to become an

outstanding player must, I think, give to it as much time and study as

he would to learning some noble science or performing well something

or other of importance; and yet for all his pains when all is said and

done all he knows is just one game. Therefore as far as chess is

concerned we reach what is a very rare conclusion: that mediocrity is

more to be praised than excellence."

|

Next time: some suggestions for more modern games that can

replace some of these and ratchet up the fun....