The latter lost power in the

year of four emperors and was ultimately succeeded by Vespasian, the

most powerful general. He started his own short dynasty, being

succeeded by his sons Titus and then Domitian. An unpopular ruler,

Domitian was assassinated. The Senate chose the elderly Nerva as his

replacement, which began the era of the "five good

emperors", all of whom but the last chose someone not their biological

son to succeed them. His successors were Trajan,

Hadrian, Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius, who ruled jointly with

Lucius Verus.

Marcus Aurelius did not manage to avoid making his son Commodus

emperor. Commodus' misrule resulted in his murder. The civil war that

followed was won by Septimius Severus, who created a strong dynasty.

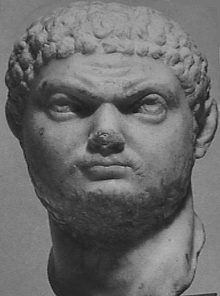

He was succeeded by his sons Caracalla and Geta as joint rulers, which

ended when Caracalla had his brother killed and Caracalla became sole

ruler.

After nineteen years of rule, Caracalla was assassinated by the

prefect of his guards, Marcrinus who succeeded him. After a year or so

he was succeeded by a rebellious army of Syria who placed the outrageous

fourteen-year old Elagabalus on the throne. In the passage of four

years, Rome's city troops had had enough; they killed him in favor of

his younger cousin, Alexander Severus, who ruled in moderate fashion

for more than thirteen years. It was during this period that Rome came

under twin threats of the Persians and Goths. Prosecuting the war

against the latter in Gaul, he lost the respect of his army

and was assassinated.

With this event begins "The Crisis of the Third Century" (235-284),

a fifty-year period that was the lowest the empire had yet witnessed.

The empire was in considerable danger and unrest and there was no

obvious successor. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the average length of rule

in this period was a mere two and a half years.

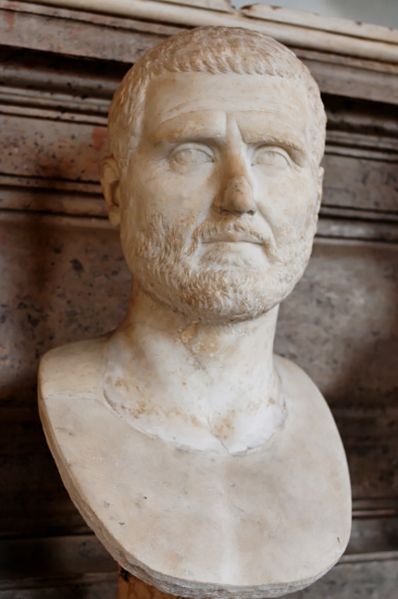

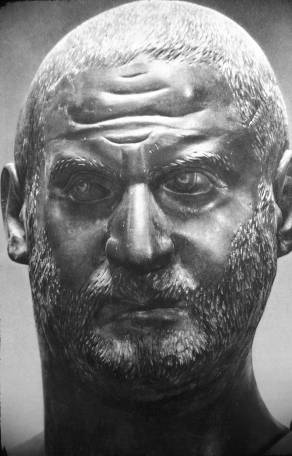

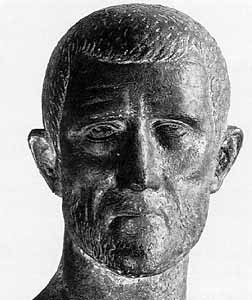

| 235-8 |

Maximinus Thrax.

A soldier who had come up the ranks from low birth, he commanded a

legion. When rather than fight Alexander Severus paid off the German

invaders, the troops killed Alexander and elected

Maximinus

their new leader. This was grudgingly ratified by the Senate, who had little

respect for his low birth, but had little choice.

Maximinus took the war to the Germans, defeating them and stabilizing

the border, allowing him to continue war against Rome's lesser, eastern

enemies. In fact he was the first emperor never to reach the city of

Rome during his reign. His harsh rule and heavy taxation brought

problems, however, and led to revolt in Africa.

|

| 238 |

Gordian I and Gordian II.

Gordian I was the governor of Africa when outraged aristocrats

murdered Maximinus' tax officials and proclaimed him and his son,

Gordian II, emperor. Much more comfortable with one of their own, the

Senate in Rome immediately ratified them as emperors.

Maximinus mobilized his army in response and advanced on Rome.

But before the Gordians could depart, Africa province was invaded by the

loyal governor of Numidia. Gordian II was killed on the battlefield

and Gordian I hanged himself.

|

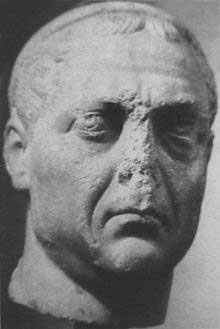

| 238 |

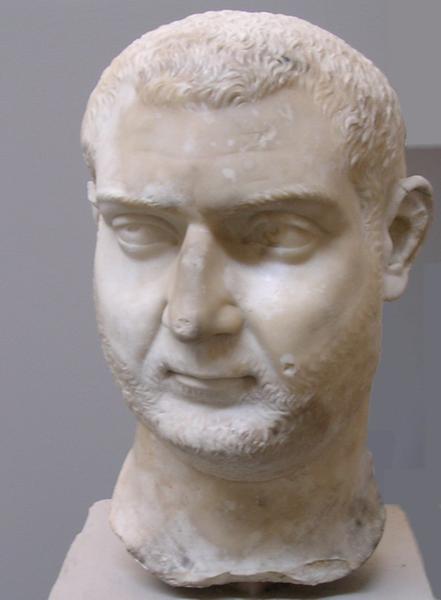

Pupienus and Balbinus.

Feeling in great jeopardy after the death of the Gordians, the Senate

elected two of their own,

Pupienus and Balbinus,

to replace them. However, these two patricians had no popularity with

the Roman people, who pelted them with sticks and stones.

Pupienus led an army against Maximinus while Balbinus ruled Rome.

Maximinus, tried to reach Rome, but on the way was forced to

besiege Aquileia, which closed its gates against him. During this time

famine and disease afflicted his army, which turned and

assassinated him, his son and chief ministers.

Pupienus and Balbinus became co-emperors, but although Maximinus' army

surrendered to Pupienus, he returned to Rome to find it in riot and

fire under Balbinus' unpopular rule.

Eventually the two stabilized Rome, but just as they were planning

war against Persia, the

Praetorian Guard stormed in, killed both and proclaimed Gordian III

emperor. The two had ruled little more than three months.

|

| 238-44 |

Gordian III.

Gordian's grandson, Gordian III, was popular, with at least some in

the city of Rome, who were loyal to the memories of Gordian I and II.

Because of their unpopularity, Pupienus and Balbinus, had been forced

to appoint him the heir, although he was only thirteen years of age,

making him the

youngest sole emperor of Rome ever. Taking advantage of his youth,

the Prefect of the Praetorian Guard ruled in his name. Meanwhile the

empire was under attack from both Germanic tribes and Persians.

A large Roman army, Gordian in tow, traveled east, drove the Persians

back over the Euphrates and planned an invasion of Persia, when the

Praetorian Prefect, Gordian's father-in-law, died under mysterious

circumstances. Marcus Julius Philippus, also known as Philip the Arab,

stepped forward to take this position. What happened next is unclear.

Persian sources claim the Persians counterattacked and won, killing

Gordian in the process. Roman sources do not mention any such battle and

claim he died far upriver. If true, the responsibility must be Philip's.

|

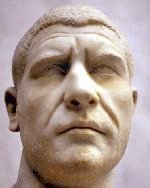

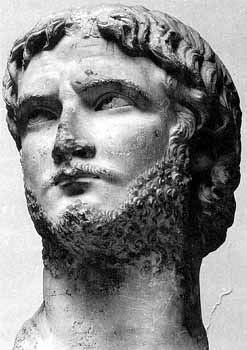

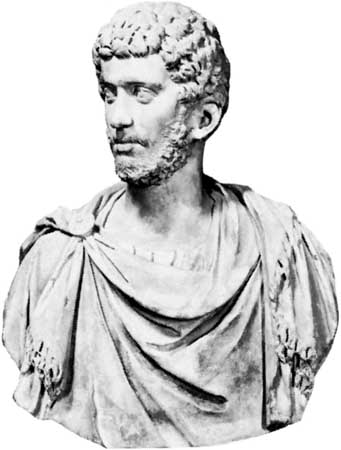

| 244-9 |

Philip the Arab.

Born in Syria, which at the time was in Rome's Arabia province, Philip

rose with his older brother in the Praetorian Guard. With his

brother's endorsement, he became Praetorian Prefect upon his

predecessor's mysterious death and was then proclaimed emperor by the

army upon this predecessor's mysterious death. Seeking to avoid

senatorial upstarts like the Gordians, he immediately made peace with

Persia – giving up Armenia and 500,000 gold denarii – and

hurried to Rome. There he was confirmed in power, but began

enormous building programs, increasing taxes and stopping payments to

the Germans to pay for it. This led to war with the Goths

and war with the Persians

over Armenia flared up again as well. Philip conducted spectacular

games and theatrical presentations for Rome's thousand year

anniversary. Amid this, three different Gothic groups and four

different generals rebelled. Philip offered to resign, but the Senate,

led by Decius, urged him to continue. Encouraged, he sent Decius to quell both

invasions and revolts. Although Decius was successful, the legions

of the Danube preferred him to Philip and proclaimed him emperor.

He marched on Rome and Philip marched out against him. Meeting near

Verona, Decius was victorious and Philip was killed, possibly by his

own soldiers who were eager to please their new ruler.

|

| 249-51 |

Decius.

Born in what is now Serbia, he was the first of many emperors to

stem from this region. He was a distinguished senator who had served

as consul, governor and prefect of Rome. Confirmed by the Senate, he

began several building projects including baths named after him and

repairs to the Colosseum following a lightning strike. He fought the

Goths, catching them by surprise, but they doubled back and turned the

same trick. Decius was the first Roman emperor ever forced to flee in

battle. Content to raid, the Goths eventually returned to their homes

while Decius reorganized his army for another assault. In this battle

in the swamp both Decius and his son were killed, possibly because

they pursued the enemy too boldly. Some claim that instead he died

because he was betrayed by Trebonianus in alliance with the Goths, but

would the legions have proclaimed such a traitor emperor?

|

| 251-3 |

Trebonianus.

Born in Tuscany, he had the typical Roman career of many military and

then political positions. He won several small skirmishes

with the Goths and became popular with the army. When he took power

with the army, the Senate back in Rome proclaimed Decius' other son,

Hostilian,

emperor. To keep peace Trebonianus accepted him as co-emperor. Like

Philip, he immediately made peace with the Goths – agreeing to

annual payments – and hurried to Rome. At this time Hostilian

disappears, possibly dying of plague. Troubles started anew in Armenia

and Persians defeated a large Roman army. Trebonianus did not respond

and the Persians successfully invaded again the next year. Then the

Goths and lesser invaders such as the Scythian tribes invaded as well.

Discontented with their emperor, part of the army proclaimed Aemilianus their

new emperor. Unwilling to give up without a fight, Trebonianus called

in his legions and prepared. The results are unclear, but most likely

he was killed by his own army and/or his army went over to the rebel.

|

| 253 |

Aemilianus.

Born in Africa province, his victory against the Goths impressed the

army who proclaimed him emperor. But he had to manage a plague in Rome

and, in the face of their attacks,

signed humiliating treaties with both the Goths and the Persians.

This hardly impressed the army.

Meanwhile, Valerian, who had been recalled by Trebonianus, was on his

way from the Rhine frontier with a large army. Aemilianus' men

mutinied on the news and killed him, accepting Valerian as the new

emperor. Aemilianus had only reigned three months.

|

| 253-9 |

Valerian.

Of a traditional senatorial family, Valerian had worked for Gordian I.

Upon taking power, the entire western empire was in disorder due to

invasions while the east was under attack by Persians. He split

responsibility for these crises with his top general and son, Gallienus.

In the east he took back Syria and Armenia from the Persians, but lost

Asia Minor to the Goths in the following year. In 259 he lost

decisively to the Persians and was dishonorably seized by them during the

peace talks, and held prisoner for life, in one report being used as a

human foot stool by the Persian emperor.

|

| 260-8 |

Gallienus.

While his father was still alive, Gallienus repelled the German

invaders in the west, winning several defensive

victories. While defeating rebels, however, the Franks broke through

all the way to Spain and the Alamanni penetrated as far as Italy, the

first invaders to do so since Hannibal. Gallienus defeated them

decisively on their retreat near Milan; they would not bother Rome

again for ten years. Then Gallienus had to put down a revolt in the

Balkans.

Taking over all the empire after his father's capture, there were

rebels in the east. Fortunately for Gallienus, they were

defeated by other Roman generals. But a revolt by Postumus in Gaul meant

that Gallienus lost control of it, plus Britain, Spain and Germany,

which now formed a separate Gallic Empire. Palmyra also gained its

independence. He also had to crush a

revolt in Egypt and more Gothic invasions in Greece while being

challenged by yet another rebel. He laid siege to the rebel near

Milan, but was murdered, by unknown hands. Most agree that because

he had lost so much of the empire and because he forbade senators from

becoming generals, most of his officials wanted him dead.

|

| 268-70 |

Claudius II.

No relation to the original Claudius, he is given the "II" only by

historians. Another soldier who had worked his way up the ranks, he

was commander of Gallienus' new elite cavalry force. When Gallienus

died he was proclaimed emperor by the army; although some accused him

of engineering his death, he magnanimously asked

that the relatives and supporters of the dead emperor be spared.

Then, with the help of his cavalry commander Aurelian, he

won one of the empire's greatest victories ever, against the Goths.

Rome took thousands of prisoners, destroyed the Gothic cavalry and

forced them back across the Danube. He then took Spain and southern

France back from the Gallic empire. But while preparing to make war

against the Vandals, he died of plague.

Tradition has it that Claudius persecuted Christians, who had to either deny

Christ or suffer. In 270 one such, a priest and physician who had provided

aid to believers in Rome, refused and was beaten with clubs and finally

beheaded. Later canonized, his name is remembered every February 14:

St. Valentine.

|

| 270 |

Quintillus.

Brother of Claudius II, he was proclaimed emperor by part of the army after his

death and approved by the Senate. He was a moderate and capable

emperor, and a champion of the Senate. However, other segments of the army

disagreed with the choice. He died at Aquileia, possibly in battle

with Aurelian or by suicide after a defeat, having served a very short

reign.

|

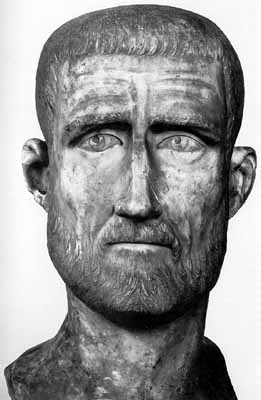

| 270-5 |

Aurelian.

Born in what is today Bulgaria, Aurelian was another soldier who rose

in the ranks, distinguishing himself as a cavalry commander in several wars.

He was preferred by much of the army, who distrusted the support

Quintillus received from the Senate. After seizing power Aurelian

engaged in a number of campaigns.

He defeated the Alamanni, the Goths, Vandals, Juthungi, Sarmatians, and Carpi.

He at last recovered Palmyra, which had taken the entire eastern

Mediterranean area, including Egypt and most of Asia Minor.

He also reconquered the Gallic Empire.

He constructed Rome's Aurelian Walls and abandoned Dacia province,

beyond the Danube. Marching to war against the Persians, he was

murdered by his Praetorian Guard, who feared his severe punishments for some

minor infractions.

|

| 275-6 |

Tacitus.

Born in Italy, he claimed ancestry from the Tacitus the historian, but

most historians doubt this. He was nevertheless a respected politician

and as such, the Senate's choice to succeed Aurelian. The army

approved, for a change, although Aurelian's widow may have ruled for a

short period. Tacitus asked the Senate to help him rule, a first in

many decades. With his half-brother Florianus he defeated a German tribe in the

Balkans. Hurrying back to Gaul to deal with another invasion, he died

of a fever, though some claim he was assassinated because he had appointed

a relative to a command in Syria.

|

| 276 |

Florianus.

Praetorian Prefect for his half-brother, he was chosen emperor by the

army without senatorial approval. His immediate concern was fighting a

German tribe, but while doing so an army in the east proclaimed Probus

emperor. The rival armies met in Asia Minor, Florianus having more

troops, Probus being the more experienced general. The latter avoided

direct battle and won a victory over a smaller part of the force.

Florianus' troops probably lost confidence in the unfamiliar climate

and assassinated him; his reign had lasted eighty-eight days.

|

| 276-82 |

Probus.

Born in what is today Serbia, he was a military tribune who later

became a governor.

He was handed the empire by Florianus' army who probably calculated

that they could get more pay increases from a grateful new emperor

than from the cash-strapped existing one.

His first act was to defeat the Goths. Meanwhile his legati successfully

fought Germans in Gaul. He initiated settling Germans inside the

empire. During his reign he had to put down three usurpers. While

marching east, Carus, the Praetorian Prefect, was proclaimed emperor by

his troops. Probus sent troops against him, but they changed sides and

like Florianus, Probus was killed by his own men, who may have

disliked his practice of using them for civic purposes like

draining marshes.

|

| 282-3 |

Carus.

Probably born in Gaul, he was educated in Rome and became a senator.

He did not return to Rome after being proclaimed emperor, but left his

son Carinus to rule the western empire while he and his other son,

Numerian, marched against the Persians. He defeated Germans and

Sarmatians along the way and marched all the way past the Tigris

River. The Persians were occupied in Afghanistan so Rome even

conquered their capital at Ctesiphon, making up for all the losses

over the years. But Carus shortly died after a storm, possibly from

lightning, disease or a battle wound.

|

| 283-5 |

Carinus and Numerian.

The brothers were co-rulers after their father's death. Carinus

hurried from Gaul to solidify his position in Rome. Numerian made an

orderly withdrawal from Persia. In Asia Minor his staff reported he

had an inflammation of the eyes and was therefore traveling in a

closed coach. After a few days a strong odor caused some of his

soldiers to open the coach where they found Numerian dead. What

happened next throws suspicion on his cause of death since the

soldiers, instead of respecting Carinus' right to rule, proclaimed

the cavalry commander, Diocletian, the new emperor. For his part,

Diocletian accused Numerian's chief aide of having killed him and then

dispatched the purported killer with his sword. Hearing this, Carinus

immediately led an army to meet Diocletian, putting down another rebel

along the way. Accounts vary, but most likely Diocletian was

victorious in battle because Carinus' army deserted him.

|

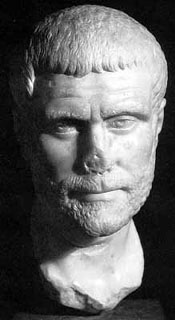

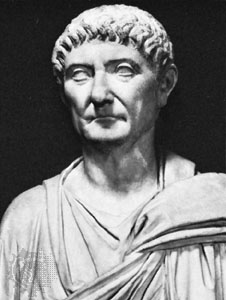

| 284-305 |

Diocletian.

Born in modern Dalmatia, he rose through the military ranks to become

cavalry commander. Thanks to his efforts the empire was finally

stabilized and the Crisis of the Third Century ended. He defeated all

of Rome's enemies and secured all of the borders. He appointed a

co-emperor and two junior co-emperors, assigning each of the four a

part of the empire to administer. He also changed the nature of the

emperor, who always before was considered simply the first among

equals. Learning from Persia and other eastern empires, Diocletian

made the emperor a remote figure who was almost never seen. He wore a

gold crown and jewels and forbade anyone else from wearing purple

cloth. Subjects who approached him had to kiss the hem of his robe;

meanwhile his image was put up everywhere. Whenever he appeared he was

surrounded by impressive grandeur. By such measures he

gave the position an aura and power that made rebellion more

difficult to attempt.

When ready, Diocletian became the first emperor to voluntarily abdicate,

taking up a life devoted to growing cabbages.

|