Spotlight on Games

>

1001 Nights of Military Gaming

- N -

- Napoleon at Waterloo

Very introductory war game given away by SPI with new subscriptions to

their magazine Strategy & Tactics. Units are army, cavalry

or artillery rated only for movement and strength. Zones of control are

semi-rigid and active. Not a bad introduction to the hobby as it is simple,

fast and fairly balanced.

- Naval War

Card game about sinking World War II enemy ships. Cards from all

nations are randomly distributed to all players so there is no strong

adherence to theme. Is actually mostly a translation of

Nuclear War to a World War II naval setting.

Later release Atlantic Storm is another way of doing a similar

thing with trick-taking. Naval War tends to degenerate

into a luck-of-the-draw and popularity contest without use of two

vitally-important variant rules: night actions and partnership.

[Take That! Card Games]

- Necromancer

Magazine war game in a fantasy setting in which two magic wielders raise forces

from the dead to fight one another over three "jewels of power"

in a many-leveled misty land. The chief innovations are that players may

convert enemy troops to their own side and that the more units controlled, the

weaker each one becomes. Unit types are similar to those of

Sorcerer

with Zombies heavy and slow, Wraiths fast and weak and Skeletons

moderate with bows and arrows. Jewels have a large possible

variety of effects which are only determined when in the actual hands of the

necromancer. Several optional rules keep the play fresh as well.

This absorbing system is very expandable for more players

simply by photocopying counters and re-coloring.

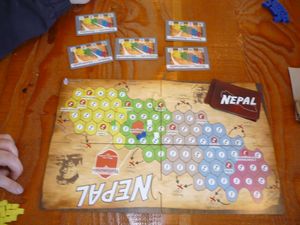

- Nepal

For such a dramatic area, too few games are set in the

Himalayas. Thus it's great to see it being treated here,

especially by an indie publisher. Steve Jones appears to be

the primary designer at Blue Panther and in shorthand it's

reminiscent of

Railway Rivals,

but with the combat rules of

Civilization

plus endgame majority control. The entirety of Nepal is shown,

dotted with towns and divided into hexagons. All players begin

in central Kathmandu (though starting at different corners

as in Railway Rivals

might have proven more strategic) and expand outwards by

placing their cubes, each turn being able to perform a

combination of three move and grow actions. Play begins with a

few public demand cards in play, meaning that the first player

to complete a chain of spaces between two towns listed gets to

place a cube on the card's most valuable points award. The

second player to do so places on the second most valuable

award, etc., but only routes which are intact by the end of play

still count. As more and more cards appear during play, there

are a couple of ways at looking at strategy. Either one goes

directly for the available cards or plays for the longer term,

trying for wide connectivity so as to be able to pick up lots

of new cards when they appear. The map is divided into five

provinces and at the end the player with the most and second

most cubes in each receives points, providing a third

consideration. All of this works okay, but is greatly

complicated and made incredibly fragile by the injection

of combat into the equation. While combat is attritional

– lowest count in a space removes a piece first, then

the next, etc. until the space's limit is reached – it's

still quite significant and potentially

destructive, as a player who refuses to cooperate

with others can sink not only his own chances, but that of

another as well. Stubborn players can get involved in prosaic,

repeated combats that allow neither to accomplish anything, which seems

to particularly occur in the area just southeast of Kathmandu.

Of course co-existing with others has its own dangers,

especially in the last round of play when it facilitates

cutting off others' routes. Unfortunately instead of

kingmaking being curtailed, the system encourages it by

providing a full extra round of play once the end has been

sighted. This also has the effect of providing a nice

advantage to whichever player goes last; considering that this

is likely to be the player who ran out of cubes and is thus

already the leader, it's the opposite of a catch-up mechanism

and exactly not what one wants. Thematically, it seems strange

that no distinction is made for mountains, which

are considerably higher in the north and west. But then the

trade routes don't appear to make any sense either. While in

the area depicted the concept of trade ought to reflect a trip, here

it seems to represent something like rails or a highway, and

yet one that can be fought over and taken over by others. It's

all very difficult to reconcile with reality. On the other

hand, the quality of the bits is pretty good, perhaps apart

from the plain cardboard box wrapped in a sleeve. The wooden

board looks like real fake wood paneling and is brightly and

attractively illustrated. The small cubes are plentiful and of

good, glossy quality. The cards are well made and there is

this unique separate wooden scoring track that looks like it

was burned into balsa with a home woodcrafting device.

Unfortunately communication design is another matter. The

board, and therefore the spaces are way too small. Each hex

tends to be so crowded with cubes that one can't tell its

population limit; they really should have been colored

differently to indicate this. Another problem are the long,

foreign town names printed on cards in a difficult to read font. At

least one player is going to have to try reading these upside

down, not at all easy. The maps on each card help, but not

enough. Between the many cards and many statuses of the various

routes determining who is doing well is so long and tedious

that one tends to not even try. With five players, which is

definitely not the ideal though three will exhibit similar

problems, this can stretch to two unhappy hours by which

somewhere in the middle everyone will only be hoping for a

speedy conclusion.

MLMM4 (Strategy: Medium; Theme: Low; Tactics: Medium; Evaluation: High; Personal Rating: 4)

Steve Jones;

Blue Panther; 2008; 3-5

- Neuroshima Hex

You may have seen one somewhere. A transparent box is filled with mouse

traps, each trap with a small ball. Now a ball is thrown in,

triggering a trap which throws two balls, which hit two traps,

throwing four balls, etc. Now imagine that as a war game.

The board shows three concentric rings of hexagons into which

players land one to three randomly drawn hexagonal pieces per

turn (reminiscent of

Attika).

Present from the start is a headquarters piece for each.

Every couple of turns someone plays a tile that activates combat.

Now each tile, in its priority order, fires at the enemies at

which it aims. Generally, being hit means the destruction of

the tile except for the headquarters which simply loses

victory points from the track instead. Each player's army has

a slightly different set of abilities. Some tiles have the

ability to enhance others; some can fire into non-adjacent

hexes and some are even able to move a

little. Actually, the latter is often a disadvantage. In a

four-player outing, the board is so crowded that it's a happy

day when one can find a useful space to place a piece, much

less be able to move anywhere. If moving is your advantage,

your days are probably numbered. Thematically this is

apparently derived from a post-apocalyptic Polish role-playing

game, but it's hard to see what kind of reality it could

represent. Forces are not marshalled or marched in any way,

but simply dropped in. And what do activation tiles

represent? This creates a reality unto itself rather than

reflecting any sensible one. But this is beside the point in

any case as any time there are more than two players there are

definite kingmaker issues. As there are already four expansion kits

– mostly adding new armies – this is essentially the

collectible card game manifested in a new way. But too often

its play is simply a mind-numbing exercise in making obvious,

limited choices.

Michal Oracz;

Z-Man Games;

2006; 2-4

LLML3 (Strategy: Low; Theme: Low; Tactics: Medium; Evaluation: Low; Personal Rating: 3)

- Nuclear War

Satirical card game about major nuclear conflagration which owes a lot to

Touring.

What would seem

to be a no-win subject actually makes for a blackly humorous experience

as players used secrets, propaganda and nuclear missiles to gradually

reduce their opponents' populations, leading to the famous phrase, "Do you

have change for twenty-five million people?"

As players get to make a "final strike" when their last population is

destroyed, it often happens that no one wins. If a player happens to

hold a one hundred megaton bomb, he can even try to destroy the world.

Anti-missiles actually borrow from the rules of Mah Jongg they

cause that player to be the one to take the next turn.

Perhaps of less poignancy

now that the Cold War has ended, but still a fast and fun silly experience.

[Take That! Card Games]

[Flying Buffalo[

[Rules]

- Nuclear War: Nuclear Escalation

Expansion kit updated flavor for the newer technologies of the 1980's

including cruise missiles, MX missiles, spies,

space platforms and killer satellites.

In general worthwhile because more options make things less certain.

Can also be played standalone, although less successfully as there

are fewer cards. Six blank cards came with the set and for these

I designed six variant cards which

were published in Space Gamer magazine, issue no. 74:

Cobalt Bomb

– Neutron Bomb

– ASAT

– Weather Control

– Orbital Mind Control

– Mole.

Douglas Malewicki & Michael Stackpole; Flying Buffalo; 1983; 2-6

- Nuclear War: Nuclear Proliferation

Second expansion adds countries with special powers, which are a bit

unbalanced and not all that interesting. But the rest of the modernizing

additions such as SCUD missiles, atomic cannon, stealth bombers and fighters,

submarines, Patriot anti-missiles, saboteurs and other cards are well

worth it. After this there were also individual cards sold, later on

grouped into booster packs.

[Flying Buffalo]

- O -

- Ogre

War game based on the science fiction story "Bolo" by Keith Laumer

(who is better known for his "Retief" series). One of the first

and still best micro-games games playable in a half hour or so,

but still containing interesting strategic and tactical decisions

for both sides, even if inside a chaotic environment of dice rolling.

Probably there are not enough dice rolls to avoid the vagaries of

the dice here, but it remains an excellent introductory war game.

Later followed on by GEV.

[Steve Jackson Games]

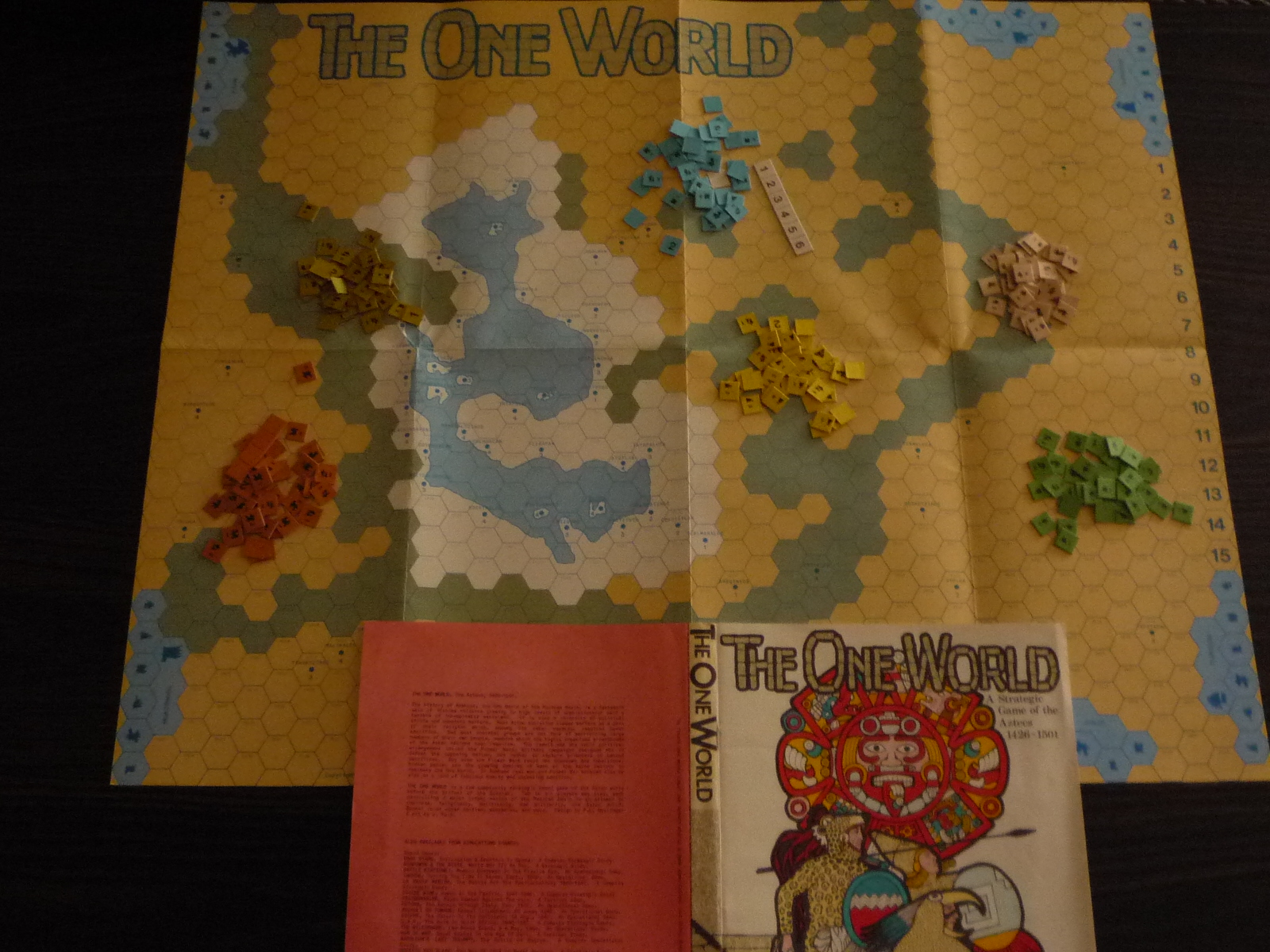

- One World: One World

Two player war game (microgame) set in a wholly-invented mythological or

fantasy world. Actually works almost like an abstract as each

player has pieces of three types, each of which move in a different way.

Combat was handled via the rock-scissors-paper technique.

An amusing romp with more playability than one would first imagine.

- One World: Annihilator

The same package also includes Annihilator,

a two-player science fiction war game in which an enormous invading robot

ship immune to energy and solid weapons must be boarded and disable from within

by space marines. Very light and subject to luck of the dice.

More adaptable than most to solitaire play.

- One World, The

War game about an obscure topic, battles of pre-Columbian Aztecs,

has some novel ideas, but does not really work without modification.

[more]

[variant]

- Origins: How We Became Human

This one is not easy to write, especially having had a hand

helping to develop it for a while. But mine was not the main

hand and not all ended up the way I wanted so there should be

at least some kind of balance in my perspective. First, let's

entice with the novelties.

In how many games can you refer to an opponent as a

Neanderthal and be correct?

In how many can you enslave another player? Or force another

to enslave you?

How many games have the kind of breadth that goes from the

development of speech centers in the brain to the atomic bomb?

This one presents human progress as a synthesis of brain evolution,

resource exploitation (taking after

Guns, Germs and Steel)

and ideas. It is

a game of efficiencies with considerable luck. On a hex map of the

world play begins with each player a minor tribe, one of

Neanderthals, Cro-Magnon, Peking Man, Archaic Humans or the

recently-discovered Homo floresiensis. This may be giving a bit too

much credence to the multi-regional theory of human origins,

but works well for a five-player game. In later eras,

Cro-Magnon is considered to have "won" and player divisions

automagically alter to become races and then nationalities as

the three eras of play proceed. Player activities are governed

by two tracks: Innovation and Population. As these tracks are

cleared by removing cubes from them to the board or brain,

players receive more and more action points. Initially the

primary actions are to draw cards and move. Later, other

activities such as domestication (à la

Jared Diamond),

resource exploitation and attacks come to the fore. The first

two depend on the roll of the die to a great extent and thus

can be cruel, though some cards help by providing die

modifiers. Combat is part of the game, but normally should be

limited to a small, sharp attack if players are aiming to win.

One of the best things players can do is play cards that gain

them elders. Not only does this clear the Innovation track and

thus afford a wide array of possible Innovation actions, but

it provides the ability to bid on Public, we could call them

civilization or achievement, cards. Available in three areas

– information, culture and administration – not only

do they provide most of the victory points, they also

confer some side advantage or disadvantage or both. Administration

cards provide an interesting example. Each turn the player

needs to perform a die roll to see whether his civilization

has collapsed. The fewer cubes he has on his Population track,

the more likely this is, but the player's best administration

card modifies the die roll to make it less likely. So this

is good, usually. But the inventor also presents the theory

that before a civilization can make progress into the new era,

it first must fail. So at a certain point the player actually

wants to fail this roll and if he has too much administration

it can be difficult. By the way, each player has a different

set of victory conditions, i.e. wants to collect just two

types of cards. But as in

Aquarius,

one action is to exchange victory conditions with someone

else, which can be cancelled at some cost by the intended

victim.

In terms of design, most great games have at least one

innovation not really seen in games before. Here we can count

at least three: (1) forces travel along hex lines and fully

occupy the three hexes around the intersection on which they

stand; (2) technology transfer occurs by one player picking up

a card from another's discard pile – very easy and

intuitive; and (3) gaining ability places something called

Elders into a pool which, when spent, are not removed, but

just go into the expended state from which they may be reset

and spent again and again – a nice representation of the

idea of capacity.

At the same time there are aspects of the game that will

irritate those sufficiently sensitive to problems of the

kind. Some are caused by attempts to bring out as much of the

theme as possible. Weather changes occur by die roll and can

severely cramp the range and options of some positions, which

may find their players with not much to do for rather long

periods of time. There are also going to be a few too many

niggly details for some, like remembering which tracks cubes

go to and come from and other matters, enough to inspire me to

create a

help sheet

to be used in addition to the one already in the game. Then

too, the discard pile system means that memory is a useful

skill which can be irritating to some. There are game flow

issues. Card draws are at the

start of the turn rather than the end, which can slow down

play. The design correctly diagnoses the potential for a runaway

winner, but solves it not by helping out those in the back,

but by creating an intentional bottleneck, that is the wait for

the very-hard-to-achieve energy level 2, which is the only way

to reach Era III. Of course this is a solution, but it's a blunt

force instrument that just makes everyone wait. The biggest

omission, however, is that there is not enough strategic variation.

Winning is a matter of playing in one kind of way, constantly

improving the Innovation track, having Elders to bid with and

progressing as fast as possible. There is no room here for an

idea such as a military victory or other kind of strategic

path. In fact, even attempting such is a major disaster as the

player who constantly fights finds himself with almost no actions and

little ability to climb out of the hole he has dug for

himself. Not only that, he puts his attackee(s) into the same

hole and, as cards are coming out at a slower than usual rate,

delays the progress of play for everyone. On the plus side,

however, this is an excellent treatment of theme. Some of its

bases are controversial, but they're often fascinating

nonetheless, such as Jaynes' theory of the

bicameral mind.

Each of the cards is labeled and illustrated with some

milestone in the human march to Progress. The

rulebook and backs of pages contain considerable background

information (in English only, while the rules themselves are in

both English and German, which is confusing at first, but

eventually assimilable).

Furthermore, the latest research and findings are often

included, such as the

recent discovery of settlements now lying beneath the North Sea.

The Diamond thesis that describes

how Eurasia had the best plants and animals while other

continents did not is somewhat departed from because otherwise

it would hardly be a balanced game. Good plants and animals are

found throughout the world.

Perhaps the single most interesting feature is one I

discovered by accident and I doubt was put in intentionally,

but comes out naturally from the research. Players often neglect

climate changes alter that the map by colonizing

areas they are not allowed to enter. To correct this tendency

I started placing translucent chips over the spaces which could

not be entered. Together these chips created lines which completely

isolate certain map areas. Sub-saharan Africa was one; the East

Asian heartland another; the rest of Eurasia a third. The

interesting bit is that this completely dovetails with what

some Berkeley anthropologists theorize must have happened in the

ancient human past: human groups cut off from one another, reduced to

smaller groups that were unable to interbreed. According to them,

anyone looking for an explanation of why there are races, and what

races are, need look no further. It's rather amazing to have this

elucidated by a game. In terms of production, having been

produced by the German printer Ludofact, this effort is head and

shoulders above anything to previously appear from

Sierra Madre Games.

True, the box is too large, but that does leave

room for expansion kits, even other Sierra Madre Games games. The

map looks good for the most part, although the use of a

saturated red over saturated blue causes the "color

vibration", used to great effect in ancient Etruscan tombs,

but somewhat jarring here. The overall footprint is also large as

besides the board, a player needs a personal display and also a

help sheet. It all just barely fits on a large table. I find

it useful to also add clear chips to remember the starting

points for the tracks and as mentioned above, for the map.

To wrap up, this is certainly not for everyone. It probably

needs more than two players to be good and at least three

hours as well. It has a few too many rules to be other than a

game for gamers. Although aiming for the German-style, it ends

up more a hybrid. Its fans will be those having patience, open

minds and above all an interest in its theme. Still, it's not

difficult in the

Chess

sense, just a bit complicated.

[summary]

Strategy: Low; Theme: High; Tactics: Medium; Evaluation: Low; Personal Rating: 7

Philip Eklund;

Sierra Madre Games

2007; 2-5

On to P

- Main

Please forward any comments and additions for this site to

Rick Heli.