|

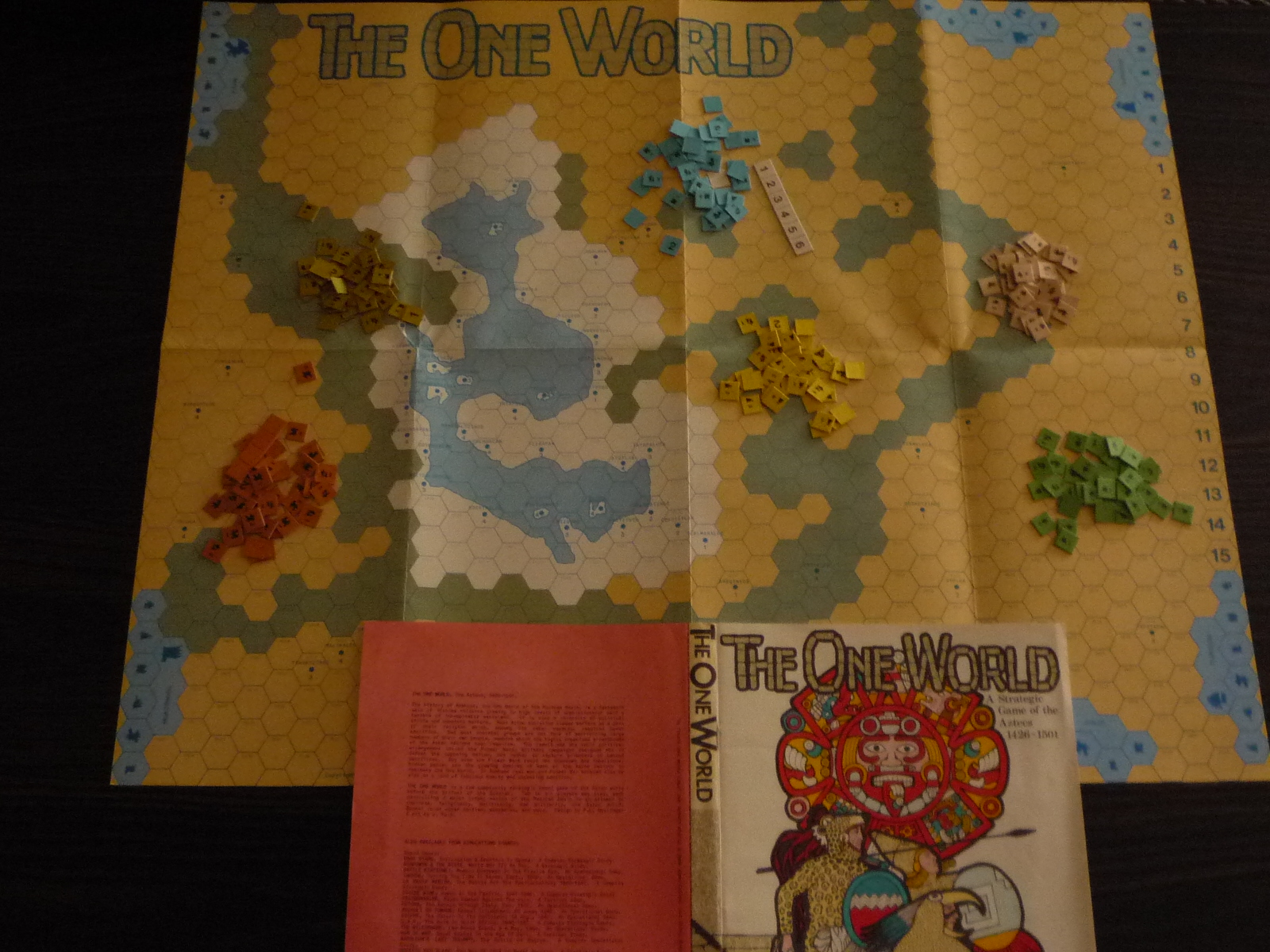

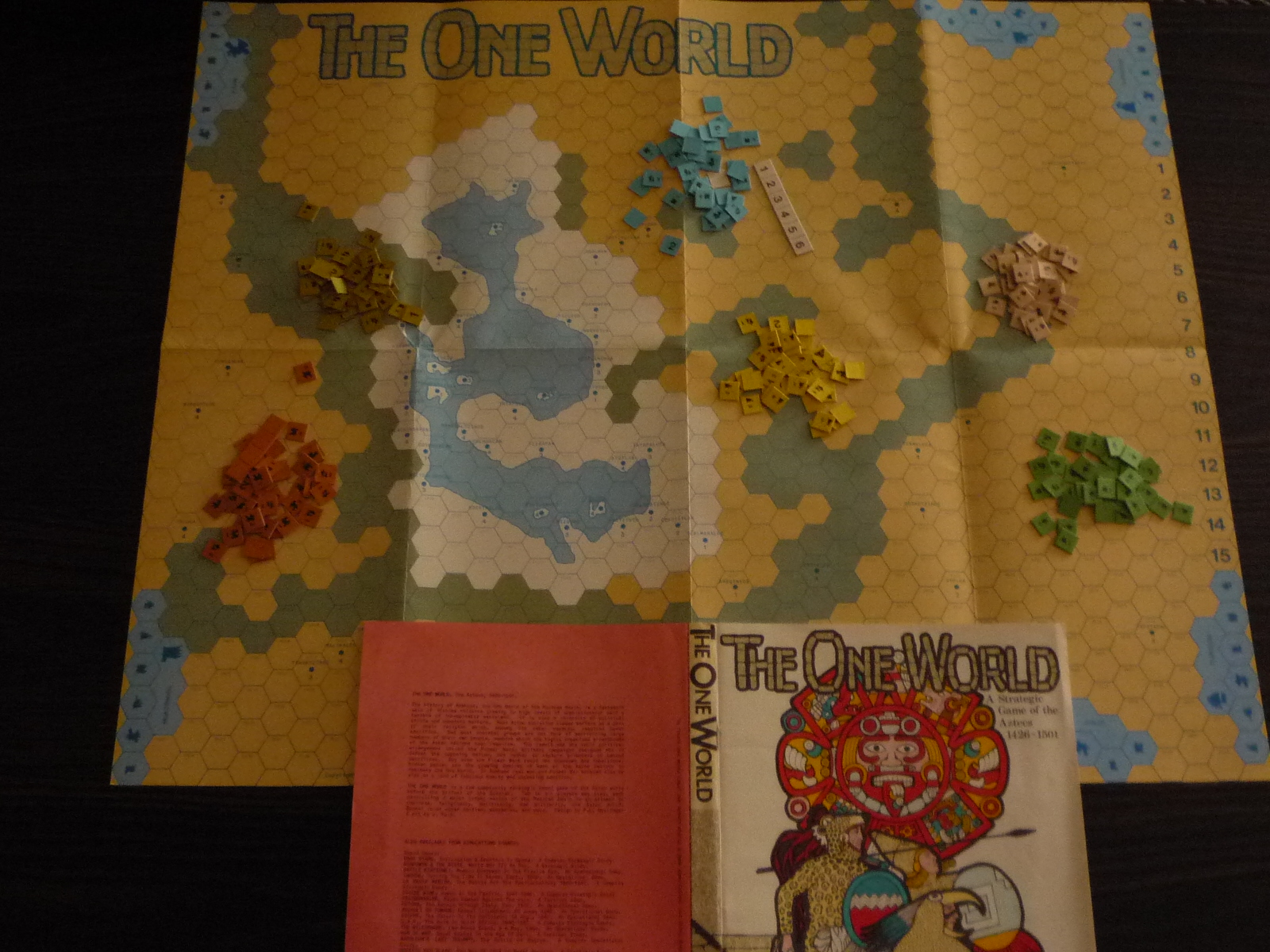

Just about every student of history will be aware of the Cortes expedition against the Aztecs, his legendary burning of his boats and the ensuing surprisingly-successful manipulation of the situation with Montezuma at Tenochtitlan, but rather fewer will be aware of the internecine Aztec warfare in the region prior to those incidents. These conflicts are the subject of The One World.The game has an attractive, colorful realization of Aztec art and warriors showing through the plastic bag (art by J. Kula). The four-color paper hex map is approximately two feet by three and includes a large number of lake hexes, settlements and à la The Crusades, fertile, barren and mountain hexes. There are also tribal tracks for up to six players (minimum four) and a game turn track, as well as five pages of rules and charts. Two hundred and fifty-five counters in six colors round out the components list.

In the game are the following tribes: Tepanscanpan, Acolhuacan, Tlahuican, Chalco, Tlateputzco and Mexica. Setup is fixed as is the turn order. All the tribes have similar units except that the Mexica can stack thirty strength points in a hex whereas others may only stack twenty. The Mexica are also more at home in the Lake, being able to move an unlimited number of units there whereas others are limited to at most five strength points there per turn. These advantages are not really decisive as the real deciding factor in the game is diplomacy, not capability.

The idea of the game is to take over cities and thereby increase one's strength so as to take over more cities and eventually drive all the other players out of the game. As in Risk then, not all players will still be playing by the time it is over, although there is a point system in use that will award victory by the end of fifteen turns if multiple players have survived. These points are awarded not just at the end, but actually at the end of each turn. So it is theoretically possible, although unlikely, for someone no longer in the game to still be the winner by the end.

In an interesting mechanism, the game features leaders whose identity is unknown until tried in combat. These leaders can improve, once, if they are successful in their first combat however, so there is strong incentive to try to use them. They tend to be replaced from combat, old age, or assassination (by the owning player if necessary) by about three turns anyway, so it is generally not a major problem to be saddled with a -2 leader.

After assassinations, players try to recruit new units based on the cities that they own and are garrisoning. Cities have Victory Point (VP) and loyalty ratings in inverse relation; that is, the more loyal a city is, the more likely it is to produce troops, but the fewer VP it is worth.

Players then undergo natural disaster table rolls which will remove from one to four units of their choice.

This is followed by the curious Flower Wars segment in which players are randomly assigned an opponent for ritual combat (historically the purpose of this was to produce victims for sacrifices in the absence of actual war which was too costly to continue on an annual basis) and then remove one or more units from the board for combat resolution later, but as far as the rules are concerned, for no apparent benefit. This segment does not seem to really work either in game or in reality terms. Every player merely assigns one unit so as to minimize losses so I have suggested a variant to improve the game aspect of it, but a more historical variant might punish a player for not having any victims taken at the end of a turn. This might give the Flower Wars more significance in the game.

Following these allocations, units move, and perhaps fly is a better term. On a map which is twenty-eight by thirty-nine hexes, units have twenty movement points. They will be slowed by mountain and lake, but the units do move quite far. This is not surprising considering that every game turn reprepsents five years, but perhaps not all that realistic considering that six different groups could cross the same area without ever meeting. For this type of operational system, it is likely that a Britannia- or even better, an A House Divided -style representation of the map would have been more effective (games by AH and GDW respectively).

Combat is via Combat Results Table (CRT) and is straightforward except that battling unoccupied cities is a bit odd. The variant contains an attempt to address this.

Following regular combat is the resolution of the Flower Wars combat with a different CRT, one which omits any retreat results. Survivors return to the map in time for counting of victory points which are granted for control of cities (only), there being some twenty to thirty scattered about the map.

To step back from the review for a moment, it has been my observation that there are players who like diplomatic games and there are players who like complex simulations, but the number who really enjoy games like this one which strongly emphasize both are rather rare. For the pure diplomatic type of player, there is too much complexity and game length for it to be enjoyable where as for the simulation player, the game is too much bound up in diplomacy to be enjoyable when what they really want to do is win by virtue of having the best strategy and tactics. One often hears this criticism expressed in a different way as "the game can't decide what it wants to be." I have tried playing twice with much different groups and with a decade between, but both games were terminated early in dissatisfaction.

Considering this issue, the obscure topic, the fact that players will be dropping out early from this game which tends to run rather long and the aforementioned rule/reality problems, it is not surprising that it has never been a big seller. The game is probably mostly of interest for those who are already strongly interested in the place and period – already because the game does not add a rich level of historical detail – who like multi-player games like Russian Civil War, A Mighty Fortress, and Holy Roman Empire and are willing to work with the rules and deal maturely with the diplomacy.

The game mentions as its historical source the book A Rain of Darts: The Mexican Aztecs (Texas Pan-American Series) by Burr Cartwright Brundage.