Uwe Rosenberg; 2000

|

Traditional; Public Domain/Pressman; c. 1000; 2

Strategy: High; Theme: Medium; Tactics: Medium; Evaluation: Low; Personal Rating: 6

|

MMHM7 (Strategy: Medium; Theme: Medium; Tactics: High; Evaluation: Medium; Personal Rating: 7)

Uwe Rosenberg; Kosmos; 2001; 3-4

Strategy: Low; Theme: Low; Tactics: High; Evaluation: Medium; Personal Rating: 6

Stephen Glenn & Mike Petty; Robot Martini; 2007; 3-4

MMMH4 (Strategy: Medium; Theme: Medium; Tactics: Medium; Evaluation: High; Personal Rating: 4)

Eddie Robbins; Winsome Games; 2009; 3-6

|

Jacques Zeimet; Zoch; 1996; 2-7

Strategy: Medium; Theme: Low; Tactics: Medium; Evaluation: Medium; Personal Rating: 7

Frank Nestel & Doris Matthäus; Doris&Frank; 1993; 2-5

Stefan Dorra;

Reinhard Staupe

Strategy: Low; Theme: Low; Tactics: Low; Evaluation: Medium; Personal Rating: 4

Reiner Knizia; Hasbro; 2008; 2-4

|

Corey Konieczka; Fantasy Flight; 2008; 3-6

Strategy: Medium; Theme: High; Tactics: Medium; Evaluation: Medium; Personal Rating: 7

Wolfgang Werner; Adlung; 2002; 2-4 [Buy it at Adlung]

MLMM5 (Strategy: Medium; Theme: Low; Tactics: Medium; Evaluation: Medium; Personal Rating: 5)

Reiner Knizia; Kosmos/Fantasy Flight; 2005; 2-5

Strategy: Low; Theme: High; Tactics: High; Evaluation: Low

Strategy: Medium; Theme: Low; Tactics: Medium; Evaluation: Low; Personal Rating: 5

|

LLHH7 (Strategy: Low; Theme: Low; Tactics: High; Evaluation: High; Personal Rating: 7)

Wolfgang & Brigitte Ditt; Schmidt-2008; 2-5

Alex Randolph; 2001

Strategy: Medium; Theme: Low; Tactics: Medium; Evaluation: High; Personal Rating: 6

| See Recent Articles |

| Vote the Next Review |

click on images for larger versions |

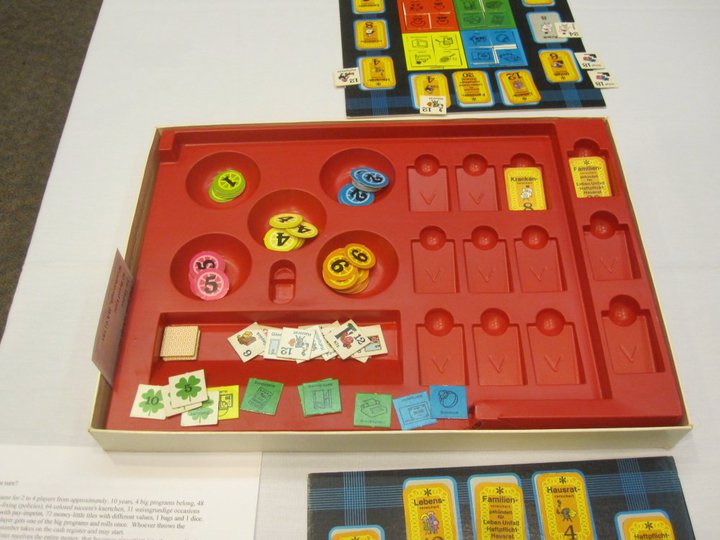

In these days of the 2010s, it's a commonplace that apart from the efflorescence of 3M Games like Acquire (1962), there are few society games from the pre-1993 period still worth playing. Yet from time to time an outlier is unearthed that still has the power to surprise us, and in a good way. One such from the early nineties was Columbus. Astron is another; it hails from the hoary mid-fifties. Splitting the time difference is this one with a punning title that means "Are you safe?" in the insurance ad sense, but which can also be interpreted "Are you sure (that you're doing the right thing?)" in the game play sense. Acquiring insurance is indeed the subject here and maybe it was originally meant as a promotional game for an insurance company, but considering that bad things can happen to players, maybe no company would want to be associated with that. Each player has a board on which tiles in four different categories – family, luxuries, investments and hobbies – are to be collected, by drawing from the bag. The double trick is that the number to be drawn is determined by die roll and that there are not a few negative events – accidents, fires, burglaries, illnesses, etc. A roll of 4 or more gives a choice of whether to risk drawing that many tiles or taking the amount in cash instead, cash that can be used to buy insurance in twelve different categories corresponding to the above events. This means that if hit by such an event, the player gets paid; otherwise a large debt is incurred, which must be paid off before the player can win. Another little decision to make is whether to save enough money to buy the family plan comprehensive insurance, which, though costing 20, is a bargain compared to the 26 one would pay to get each of its four policies individually. There are also a few good events in the form of monetary windfalls; these are a double advantage as not only do they help, but they take the place of something which might be negative. Possibly considered as a catch-up mechanism, it's not clear if these were really necessary or even good for the design. The other important rule is that since no player is likely to draw exactly the advantages needed, any duplicates are purchaseable by others (at a cost of six). Although the plastic insert, designed to be used like a banker's tray is quite clever, the tiles in this era were rather thin and cheaply made and illustrated. The small cards are okay and look a little better as well. Talents needed for this game are noticing what has already been drawn (similar to the very dissimilar Empires of the Middle Ages) and from this data forming a good idea of how dangerous drawing a lot of tiles might be as well as assessing how well one is doing and taking risks accordingly, i.e. small if in the lead, but large when trailing badly. So even though this is quite random, this risk-taking can be quite exhilarating and for schadenfreude fans, it's not bad seeing someone else draw a particularly nasty event either. Players of Sticheln will understand.

LHMH7 (Strategy: Low; Theme: High; Tactics: Medium; Evaluation: High; Personal Rating: 6)

Rudi Hoffmann; Spear's Games-1971; 2-4; 60 [Shop]

Franjos

- Better artwork/layout on some of the cards and player aides.

- Print a simple board on the back of the player reference card and before their first game let players play out the dungeon traversal. Because before your first game it's really hard to understand what the consequences of your tile placements are going to be, yet you spend the bulk of the game's time in this preparatory stage.

- For marketing purposes, a better title as the current one doesn't tell much about what the game is really like.

- In our game one of the public rewards was to the player who has the most treasure chests, but no treasure chest ever appeared.

Alan R. Moon

Update of July 10, 2008: There is now a nice free online version which, of course takes care of the accidental wrong response problem. Be careful however as there is a serious bug. If the person creating the game does not choose himself as player 1 and then immediately after creating the game goes at his cards, he instead gets to see all of the cards of player 1, quite an unfair advantage. [6-player Games]

Michael Schacht; Berliner Spielkarten; 1997; 3-6

Strategy: High; Theme: Low; Tactics: Low; Evaluation: Low; Personal Rating: 6

Reiner Knizia; Kosmos; 2006; 2-4

Strategy: Low; Theme: Low; Tactics: High; Evaluation: Medium; Personal Rating: 6

|

MMHM6 (Strategy: Medium; Theme: Medium; Tactics: High; Evaluation: Medium; Personal Rating: 6)

Richard Breese; R&D Games; 2009; 3-6 [Shop]

Uwe Rosenberg; 1997

Uwe Rosenberg; 1998

Uwe Rosenberg; 2003

Strategy: Low; Theme: High; Tactics: High; Evaluation: Medium; Personal Rating: 5

|

MMHM7 (Strategy: Medium; Theme: Medium; Tactics: High; Evaluation: Medium; Personal Rating: 7)

Mike Fitzgerald; Abacus/Rio Grande; 2009; 2-4

Strategy: Low; Theme: High; Tactics: Low; Evaluation: Low

Strategy: High; Theme: Medium; Tactics: High; Evaluation: High; Personal Rating: 5

Martin Wallace; Warfrog; 3-4; 2007

John Harrington; Fiendish Games; 1991; 2-9

Personal Rating: 6

- simple, but fast turns make it strangely addictive

- tends to resemble kiddie soccer with every player clustering around the ball

- really what one wants to do is align players with the ball, horizontally or (especially) vertically so that they can either claim a loose ball or be passed it from a teammate, as well as block the opponent. On rolls where that is not possible, one wants to align players with other players so that in the event they do get the ball, they can be passed it. So in a funny way it's all about keeping all of one's players in nice, neat lines. This should appeal to people who enjoy organizing things.

- would be tempting to try some variants, e.g. a forced kick goes one space less, an unforced one has the option of going one space more. Maybe too players could try to foul, either stealing the ball from its holder or displacing an opponent away from the ball, and having a chance to get away with it or else take a yellow card.

- It would also be tempting to let players roll two dice and choose which one to use, but probably that would be a mistake as the fun depends on the quick turnaround of turns.

- Production could use a bigger board and if every fifth line were indicated the counting would be easier.

- The pawns are too small and always falling over, especially when there's a crowd of them. It would be easier too if the ball were somehow a hat or ring that could be placed on top of a pawn rather than a disk under it that has to constantly be fished out.

- Four hours is mentioned as a possible maximum playing time.

Strategy: Medium; Theme: Low; Tactics: High; Evaluation: Low

|

Jens-Peter Schliemann & Bernhard Weber; Zoch/Rio Grande; 2007; 2-4

Strategy: Low; Theme: High; Tactics: High; Evaluation: Low; Personal Rating: 7

Jens-Peter Schliemann & Bernhard Weber; Zoch/Rio Grande; 2007; 2-4

Strategy: Low; Theme: High; Tactics: High; Evaluation: Low; Personal Rating: 7

|

HLMH5 (Strategy: High; Theme: Low; Tactics: Medium; Evaluation: High; Personal Rating: 5)

Stefan Feld; Alea-2011; 2-4; 90-120

Update: Played again in 2010, i.e. almost a decade after the initial release and fascinatingly almost all of the then bad ideas have now turned out rather successful. Never has "ahead of time" been more aptly illustrated. [Take That! Card Games]

LHMM5 (Strategy: Low; Theme: High; Tactics: Medium; Evaluation: Medium; Personal Rating: 5)

Rich Koehler; Cool Studio; 2002; 2-4

Strategy: Low; Theme: Low; Tactics: Low; Evaluation: Low; Personal Rating: 7

|

Emanuele Ornella; Amigo; 2008; 3-6

MMMM7 (Strategy: Medium; Theme: Medium; Tactics: Medium; Evaluation: Medium; Personal Rating: 7) [Shop]